Utilizing Interaction to Elicit Player-Character Empathy in Ways Impossible with Other Mediums

- joshuabresler

- Sep 24, 2019

- 14 min read

Abstract

While mediums such as novels, movies, comic books, and theater have their own tools to evoke empathy in their audiences, video games have introduced a new approach, allowing audience members to actively participate in the decision-making process of the characters on screen. Analyzing two key games – Spec Ops: The Line (2012) and The Last of Us (2013) – as well as a third, shorter example, this paper will evaluate how to leverage the full potential of player-character interaction to pull the player through the ‘walls’ of storytelling.

Introduction

There are walls in every form of storytelling, which separate the audience from the story being told. In books, the page itself constitutes this wall. In movies and video games, the screen acts as a barrier. Unlike the fourth wall, this is not one you can simply step through at will, forcing your audience to become part of the story. Instead, it is one that you must entice your audience - entirely unaware not only that you are attempting to do this, but that the wall even exists at all - to step through themselves. They must be fully engrossed and believing in the story being told, so much so that real life falls away.

In regards to written or spoken word, stories can be told in the first person. In a comic book, pages are divided to represent the action or emotions being expressed. In movies, visuals and sound are introduced into the fold. So what makes games different from all of these other mediums? The player interacts directly within the story.

As so many people will reiterate over and over, we as humans are social creatures. Due to thousands of years of evolution, people are hardwired to do everything they can to fit in with others around them. Our animalistic tendencies can be leveraged in many different ways, but now that we have access to the tool of interaction we can tap into some of those most deeply rooted. That is the reason novelists oftentimes use the first-person perspective when trying to have a relatable character. We are reading from the character’s perspective. We may even believe for some time that we are the character, throwing out the inhibitions of the real world around us. Frequently, this works miraculously, but sometimes, there is no substitution for the real thing. In video games, we don’t just believe ourselves to be the character, we are the character. We make decisions for them sixty times per second, and each of those decisions can lead them to fame and fortune or death and destruction. In a novel, it would be nearly impossible to make the audience feel a sense of teamwork – real teamwork – because they had no real stake in the process. In video games, we can.

The amount of control a player has can be tuned all the way from an interactive story to a perfect sandbox. Manipulating this may convince the player that they have full control and that they made the decisions on-screen while in actuality, being carefully manipulated to make those exact decisions.

Spec Ops: The Line

A game that illustrates this concept extremely well is Spec Ops: The Line. While severely overlooked by players, the writers knew exactly what they were doing. The player is placed inside the mind of a mentally unstable soldier sent to help an evacuation attempt in Dubai, but ends up committing horrific acts – including war crimes – most of the time entirely unaware that that is what they are doing (at least until the game explicitly shows them the results).

One such example is when Walker – the playable character – comes across a massive group of enemy soldiers. The player is told that they have to use white phosphorus to take the enemies out. In most cases, the player does not even question the game before committing the act.

Only after the player makes their way over to the bodies do they realize that they slaughtered not only soldiers – who turned out to be allies - but also the civilians in their care. This specific example utilizes multiple psychological techniques to coerce the player into committing a horrifying act. The first of the two is the foot-in-the-door technique.

“The foot in the door technique (Freedman & Fraser, 1966) assumes agreeing to a small request increases the likelihood of agreeing to a second, larger request.”

(Simply Psychology, 2014)

By convincing the player to commit smaller acts such as taking out enemy soldiers that are hostile, then soldiers that are supposed to be friendly, but are attacking Walker and his crew instead, up to the execution of one of two men who supposedly committed serious crimes, they can ramp up the acts to the point where using white phosphorus on unknown targets seems at least semi-legitimate as a tactic.

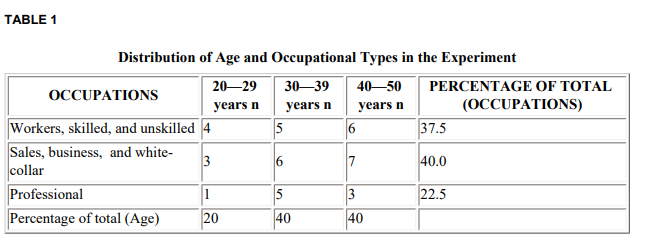

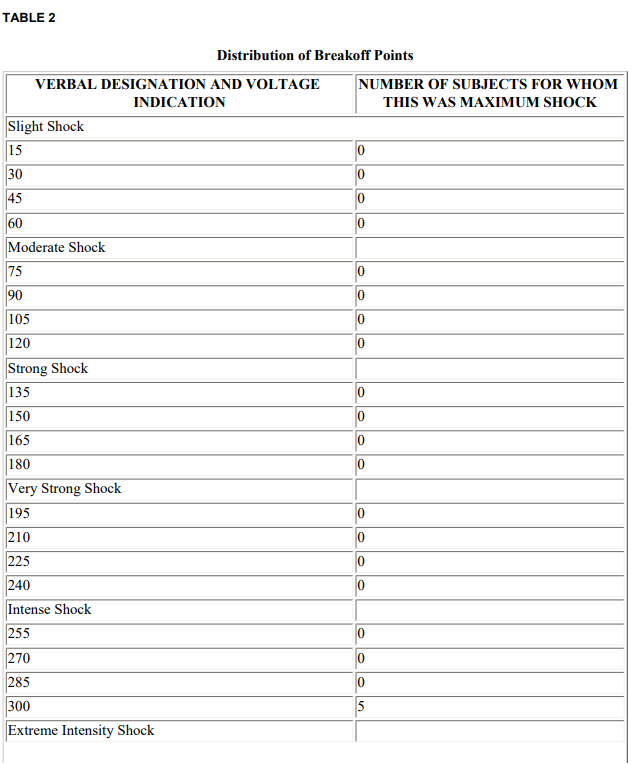

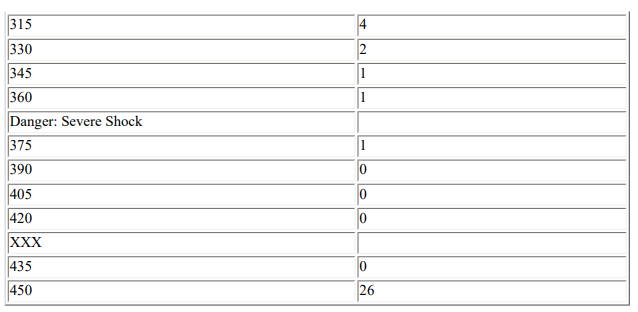

The second technique was studied in an infamous experiment by Stanley Milgram, published in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology as Behavioral Study of Obedience - more commonly referred to as Milgram’s Experiment or Milgram’s Obedience Study – in 1963. In this study, scientists told subjects that there was another subject hooked up to electrical wires. If the second subject either did not answer or answered incorrectly, the first subject was to press buttons that administered electric shocks of increasing intensity. In reality, the subjects “receiving the shocks” were actors, but the first subjects were real, everyday people. Nearly 80% of subjects administered 300 volts of electricity before ‘defecting’. In the end, even after the second subject had become unresponsive, subjects continued to administer electric shocks, and by the end, 65% of subjects complied with a shock that they knew would kill the person in the other room simply because the scientist in the back told them to continue.

(Milgram, 1963)

In Spec Ops: The Line, John Konrad – the man the player has been sent to assist – continuously talks to the player over the radio, telling him to commit heinous acts to protect civilians. When it turns out at the end that Konrad had been killed before the start of the game, and the voice was actually inside Walker’s head, the player realizes the true extent of what they have done.

«Spec Ops: The Line» y la cuarta pared de arena. (2016, August 10).

Now, there is the argument to be made that in almost all cases in-game where a choice is presented, the player has no actual choice, because they cannot progress if they do not complete those tasks. However, as the game constantly states in its loading screens, that is the other option: do not progress. Shut the game down and walk away.

Frye, B. (2014, July 11). These Loading Screens from Spec Ops: The Line are Chilling.

Frye, B. (2014, July 11). These Loading Screens from Spec Ops: The Line are Chilling.

Frye, B. (2014, July 11). These Loading Screens from Spec Ops: The Line are Chilling.

This, however, will only happen in the rarest of circumstances, due to a multitude of reasons, including the fact that the most obvious answer is oftentimes overlooked, the ‘nirvana fallacy’ (falsely comparing an actual solution with an impossible, idealized one), and the ‘sunk-cost fallacy’ (which states that the more resources a person has poured into something, the more likely they are to continue, even if the end goal will cost them even more).

Despite the fact that shutting off the game is a legitimate option, players will very rarely even consider it. Still, the knowledge that they did continue could have been implanted in the back of their minds, whether consciously or not – cued on by the loading screens.

The Last of Us

The second game I will be analyzing is The Last of Us. Almost no game in history has done a better job at embracing psychology to create empathetic characters than this one. Immediately from the opening sequence, The Last of Us packs a multitude of techniques to make the audience empathize with the on-screen characters. In the first iterations of the game, before being released to the public, the player would only control Joel, a simple, everyday father who within the span of one evening (or 10 minutes of gameplay) goes from joking around with his young daughter past her bedtime to clutching her as she dies in his arms.

The Last of Us Gameplay

At first, the climax of that specific scene was sad, but not quite at the level that Neil Druckmann – the Creative Director on the game – wanted. For a while, he could not figure out why. The acting was superb, the scene was set up perfectly, but it wasn’t quite fitting into place. Finally, “Someone suggested the idea of, well, what if you were to play as Sarah?” (Druckmann, 2013). Playing, even just for a few minutes of the introduction, as Joel’s daughter worked miraculously.

Exclusive | Grounded: The making of The Last of Us

The player wakes up as Sarah to a phone call from Joel’s brother, Tommy. It is the standard “Something’s wrong, get help” phone call you see in every pandemic story ever, but it nonetheless sets the tone. The player can then walk around the room lethargically, getting a feel for Sarah as a character; who she is, what she likes, what kinds of birthday notes she writes to her dad, all the things you might expect of a twelve-year-old girl in 2013.

Eventually, the player will wander over to Joel’s bedroom, only to find it empty, the news running on the television. Suddenly, the scene around the reporter will intensify, with people running and shouting, before it cuts out. At the same time, an explosion will rock the room, and be visible from the window.

The Last of Us Gameplay

Many times, while watching television, or reading the news, event schemas will cause us to brush off horrific events if they are far away – also referred to as construal level theory. It is the idea that ‘if it does not affect me, it is more abstract and therefore less important.’ If the game had only shown the television cutting off, it might be concerning. Even just the explosion itself would have been very concerning, but by connecting the television and ‘real world’ of the game, it gives the immediate pending anticipation of danger. “This is what is happening, and this is how far away it is.” We see the faces of the people killed in that explosion, and they were in the bedroom talking to us only a second prior.

We can see this in Sarah as well. She crosses her arms and shouts for her dad. Her walking animation becomes far more brisk, alert, and stable as though she is bracing for an unknown attack. What that does more than anything though, is tell the player “This is what you should be feeling.”

If somebody near us is feeling a certain way, we will mimic their actions, because that is how we survived thousands of years ago. We look to the most innate actions; the dilation of a pupil, the tensing of a jaw, an increased breathing rate. If the person sitting next to you in a lecture is tapping their leg incessantly, whether logical or not, chances are you will feel at least some primal fear. In psychology, this is called ‘mimicry.’ If this scene had taken place in a film, we would have been able to see Sarah’s actions, heard the fear in her voice, but having taken controls of where she walks, what she looks at, how quickly she approaches an area, whether she walks around, wildly looking for her father or peering over the staircase banister before moving on ahead, we actually place our survival instincts onto this little girl. How then, could we not mimic her actions if we believe ourselves to be her.

This is exactly the point of playing as Sarah for the first part of the opening rather than Joel. When she reacts, the audience reacts. When the audience wants to look around the truck as Sarah and Joel attempt to escape the area, Sarah looks around. The audience and character are one and the same.

So when Sarah breaks her leg, the character control switches to Joel. You – assuming the role of the player – must carry your daughter to safety. Just as you think you have succeeded, a dark, silhouetted soldier walks up, mumbling into his radio before shooting at the two of you. Suddenly, you have an immediate fear for your life. When Tommy saves the two of you, you feel relief. And when you, as Joel, look over and see your daughter clutching her chest, sobbing, you feel the need to protect her, to find a way out. And when she dies in your arms, despite everything, despite what you had been promised by the sheer fact that children cannot die before their parents, you, as the player, feel the same way any father would. As though a piece of you died too.

Because it did.

Because you played as Sarah.

The Last of Us Gameplay

Twenty years later, Joel is forced to partner up with a fourteen-year-old girl – Ellie. The two of them are lukewarm at best when they first meet, but slowly, over the course of the game, find a surrogate father-daughter relationship in each other.

At one point, they both have to work together to make a dam crossable. As you walk past as Joel, Ellie offers the player a high five and says “teamwork.” The player can then proceed to either press triangle to give her a high five, or walk on past.

If you decide to walk past, she will badger you about it, saying “Really? Just gonna leave me hanging?” If you continue to ignore her, she has a few more quips: “All right. I see how it is. It’s just a high-five. It takes like 5 seconds.” If the player does, in fact, decide to give her a high five, she will simply say “Yeah,” an immensely satisfying response for something so simple.

Neither of these options affect anything down the road, they do not even affect dialogue later in the game. Their purpose is simple; make a very linear-story driven game feel more open. Also, this is not the only situation in the game where that occurs, so it does not feel out of place in a very linear game.

Giving the player an option on something so trivial, provides the illusion of far more control than is real. Usually, developers attempt to achieve the same result in far more complicated ways, such as providing multiple possible paths through level design or increasing the options on how to tackle a specific problem. While those are extremely viable options, so is simply animating a high five.

Even further along, the game pulls the same trick as at the start. Control switches from Joel to Ellie. Immediately prior to this switch, it is hinted that Joel may have died. The opening scene introduced the idea that the current playable character is not necessarily going to survive, and this scene takes advantage of that. A trope has been established, even if it only occurred once before. The only time that it did happen, a lead character died. No piece of the game ‘promised’ that Joel would make it to the end, only that Ellie might. The two of them had reconciled. Joel trusted Ellie enough to take care of herself. For all intents and purposes, Joel’s story arc could have ended there if the designers had so wished. Even so, not even once did the game actually state that Joel had died.

We instinctively put unrelated pieces of information together and try to figure out how they align. This is how cuts in film work. Therefore, in The Last of Us, the designers played entirely upon tropes and patterns established not only earlier in-game, but in other works of every nature to make the player see and believe something that was not there.

The Last of Us Gameplay

Later, in the section where Ellie is the playable character, there is a point where all weapons and tools, save a switchblade are taken away. Ellie is meant to feel smaller and weaker than Joel, so this gameplay decision is massively purposeful. The player needs to sneak around; cannot run headfirst into fights. When she does manage to find a pistol, there is only one bullet left, and she has to scavenge to get enough to stand a chance in a gunfight, especially in more difficult modes. If playing on one of the higher difficulties, the player might be lucky to find four shots throughout the level. Even then, it is pointless to fire them unless in a situation where there is no other option, because the sounds of the gunshots will send everyone running directly towards your position.

When Ellie finally manages to kill David – the main antagonist that has been tormenting her - the player is meant to feel conflicted. After playing through the game, one person commented that at first, he felt relieved, due to the fact that Ellie (and by extension himself) was safe, then shock and excitement as this truly evil man met his end. He then realized what had happened to Ellie, how it affected her, and felt sad, then angry at the situation, before a feeling of “melancholia” after Joel pulls her away, calling her “baby girl,” a term he had reserved the entire game for his daughter by birth; Sarah. All of these emotions, every basic emotion (Ekman, 2005, pgs. 45-60), within a matter of seconds. If not for tapping into our primal instincts, there would have been no way for the game to have caused an average person to switch so completely in such short periods of time.

The Last of Us Gameplay

As stated earlier, it is possible to tune the amount of control a player has, all the way to either end of the spectrum. Throughout The Last of Us and all of Naughty Dog’s more recent games, they have implemented an extreme range of levels of control. Rarely does the game jump directly from gameplay to cutscene. Oftentimes, there are middle-states to smoothly transition, or fully avoid a fully scripted moment.

For example, while playing as Sarah at the start of the game, the player may look and move around in the back seat of Tommy’s truck. They cannot do anything beyond that, but it keeps the scene from falling into the category of either a cutscene, no different from watching a movie. At other times throughout the game, the player may be locked into a sniper rifle, not being able to physically move around, but still able to adjust the scope. Sometimes, the player has only the control of hitting a button at the right moment, such as when Joel is trapped in a bus near the end of the game and has to grab onto a ring to stop himself from slipping back even further. In that particular scene, even if the player hits the square, circle, or x buttons rather than triangle as the game instructs, the game will accept it, because the purpose is to create a sense of urgency and panic. It is about hiding the moments when there is no control, always making the player feel as though they can decide what to do, even if that option does not really exist.

Uncharted

In his 2013 Keynote for the International Game Developers Association, Druckmann brought up even a third example, which the team at Naughty Dog had previously attempted to put in a game. In Uncharted 2, there were hopes to do a scene with a Nepali mute girl. The girl would have woken Nathan – the protagonist of the game – in the middle of the night and guided him to a rooftop overlooking her war-torn city.

“And it was, in our minds … a really beautiful moment of how you can bond with someone through gameplay.”

(Druckmann, 2013).

This is not in any way to claim that true freedom in gameplay must be removed in order to make a better story. If that were the case, the player would oftentimes have no physical reason to continue the story. Both work in tandem to create these emotional beats.

“If you tell certain stories, your game doesn’t have to be fun. I actually disagree with that. I think your game has to be fun.”

(Druckmann, 2013).

Conclusion

The one tool we have to differentiate ourselves from other mediums – an incredibly powerful and diverse tool – is finally beginning to be understood in a way that encourages players to forget the world around them and fall headfirst into the world presented to them. Breaking down the walls of storytelling has never been more accessible, and while not every story should be told as a game, there are many that could benefit greatly from it. As shown with the recent successes of games that have exploited this opportunity, players support this change not only with words and reviews but with money and time. We use stories to understand ourselves, to understand others, to escape from the world. Why would we not want to employ such a tool and break down those walls?

Citations

Naughty Dog LLC. (2013). The Last of Us [Playstation 3]. Los Angeles, CA: Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Yager Development. (2012). Spec Ops: The Line [Xbox 360]. Berlin, Germany: 2K Games

Mejmil. (2016, December 31). IGDA Toronto 2013 Keynote: Neil Druckmann (Stereo Audio). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RjwuPeqZt0s

Europe, P. (2014, February 24). Exclusive | Grounded: The making of The Last of Us. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0l7LzC_h8I

McKee, R. (1997). Story: Substance, structure, style and the principles of screenwriting. New York: ReganBooks.

Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,4(2), 195-202. doi:10.1037/h0023552

Huizinga, J., & Schendel, C. V. (1972). Homo ludens. Torino: Einaudi.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371-378.

Friedman, D., Pommerenke, K., Lukose, R., Milam, G., & Huberman, B. A. (2007). Searching for the sunk cost fallacy. Experimental Economics,10(1), 79-104. doi:10.1007/s10683-006-9134-0

Ekman, P. (2005). Basic Emotions. Handbook of Cognition and Emotion,45-60. doi:10.1002/0470013494.ch3

PsycNET. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/record/1987-14675-001

Keen, S. (2006, August 09). A Theory of Narrative Empathy. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2010-25761-002

Frye, B. (2014, July 11). These Loading Screens from Spec Ops: The Line are Chilling. Retrieved from https://www.cgmagonline.com/2014/06/06/loading-screens-spec-ops-line-chilling/

«Spec Ops: The Line» y la cuarta pared de arena. (2016, August 10). Retrieved from https://lattetotheparty.wordpress.com/2016/08/10/spec-ops-the-line-y-la-cuarta-pared-de-arena/

Frye, B. (2014, July 11). These Loading Screens from Spec Ops: The Line are Chilling. Retrieved from https://www.cgmagonline.com/2014/06/06/loading-screens-spec-ops-line-chilling/

McFadden, M. (2016, June 17). Ellie kills David (The Last of Us). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5XusvWDbpM

Push Square. (2015, February 02). Watch Teens Get Choked Up by The Last of Us' Opening Scene. Retrieved from http://www.pushsquare.com/news/2015/02/watch_teens_get_choked_up_by_the_last_of_us_opening_scene

Spec Ops: The Line's writer says everyone on it would 'rather eat broken glass' than make a sequel. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.videogamer.com/news/spec-ops-the-lines-writer-says-everyone-on-it-would-rather-eat-broken-glass-than-make-a-sequel

Meo, F. D. (2016, November 01). The Last of Us Remastered Gets PS4 Pro, HDR Patch; Comparison Screenshots Shared. Retrieved from https://wccftech.com/last-us-remastered-gets-ps4-pro-hdr-patch-comparison-screenshots-shared/

Comments